GPT2 is unigram-ist

There is much literature investigating the “long tail” robustness of machine learning models and methods to combat underrepresentation of important data points.

Luckily, for language, the “long tail” isn’t that important to achieve fluency - the basics of English depend mostly on understanding the interplay of frequent words, such as prepositions and how they dictate sentence structure. However, as language models scale and their stakeholders diversify, the “long tail” becomes increasingly important as the only source of further improvement. Complex tokens arising in specific biological contexts or obscure legalese terminology are all use cases we would like a generally powerful LLM to be able to interact with. We would also like the LLM to be as strong as possible in low-resource languages like Zulu, despite not having much training data (and robust to jailbreaks).

Unfortunately, this is quite a difficult task, though advances are being made. Finetuning, oversampling/other training time tricks, and clever prompting can remediate the issues. However, it seems to me that if these techniques do not induce significant changes to the weights or training process, the “long tail” problem will always plague models trained using empirical risk minimization - the size of the $\varepsilon$ and $\delta$ probabilities in PAC learning theory are actually relevant.

In this post, I’ll describe a method that demonstrates how GPT-2 models are unigram-ist - they “discriminate” based on unigram frequencies and represent extremely infrequent tokens differently in their embedding matrices.

Latent Training

The setup is standard. Assume the token space is $\Sigma$ with $|\Sigma| = N$ and that the true unigram frequency density function is $f \in \Delta(\Sigma) \subset \mathbb{R}^N$, where $\Delta(\Sigma)$ is the simplex of density functions over $\Sigma$. Assume we have whitebox access to the unembedding matrix $W_U \in \mathbb{R}^{d_m \times N}$ of a standard autoregressive decoder-only model $m : \Sigma^* \to \Delta(\Sigma)$, where $*$ is the Kleene star and $d_m$ is the latent model dimension.

We will train a latent $x \in \mathbb{R}^{d_m}$ that elicits $f$ when unembedded and converted from logits to a density. Formally, we want

\[\text{Softmax}(W_Ux) \approx f.\]For the less intuitive way to think about this setup, notice that it is equivalent to training a constrained linear probe that takes an input token and predicts the unigram frequency.

For the true unigram values, I take $2000$ data points from OpenWebText, tokenize them, and aggregate the frequencies as an approximation (resulting in ~1e9 total tokens). For tokens that never appeared in this random subset, I add a “ghost count” so that log probs are still possible. I use the Stanford suite of open source GPT-2 models.

I train a latent using gradient descent1 on an MSE-based2 loss function in log-prob space:

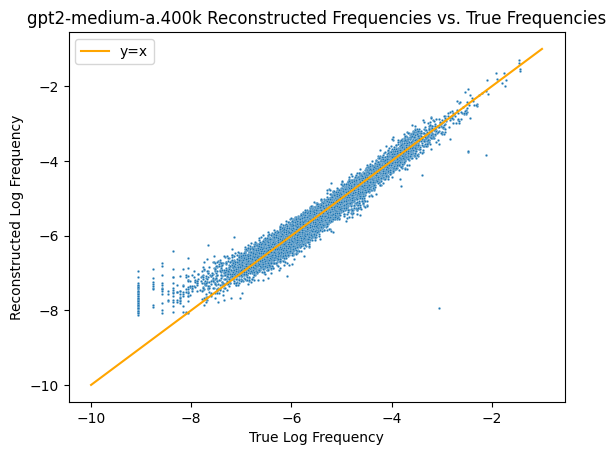

\[\bar{x} = \arg\min_{x \in \mathbb{R}^{d_m}} \| \log\text{Softmax}(W_Ux) - \log f\|_2.\]Below, I’ve plotted the results for the final checkpoint of seed a of the gpt2-medium models. On the x-axis is the true frequency ($f$) and the y-axis is the reconstructed frequency $\hat{f} = \text{Softmax}(W_U\bar{x})$.

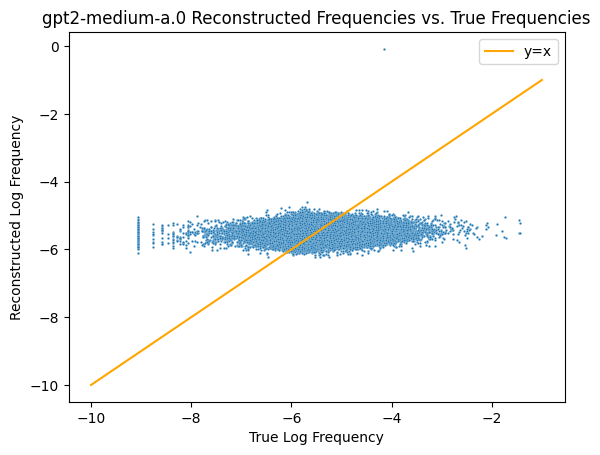

To double check that this actually represents how well the unigram frequencies are being linearly represented, we can check the plot for the initial checkpoint when $W_U$ is still random.

As expected, this comes out revealing that there’s no information encoded in random weights, so the previous results aren’t spurious.

As expected, this comes out revealing that there’s no information encoded in random weights, so the previous results aren’t spurious.

What we can see on the tail in the first graph is that the embedding matrix has essentially created a “tokens that occur in the training set with probability less than $10^{-k}$” bucket - it systematically overestimates the probability of these low frequency tokens. It’s likely that because the model doesn’t get to see enough appearances of these tokens, the embeddings are improperly formed. There are a few other non-mutually exclusive explanations for this behavior that I can think of:

- The model can only output distributions in a $z-1$ dimensional subspace of the larger $N-1$ dimensional $\Delta(\Sigma)$ (the $-1$s come from normalization). If it had to save space, it would cut corners on properly representing the low frequency tokens first.

- The model doesn’t want to incur significant loss in the training set when the token actually appears. So, it “hedges” to prevent underconfidence on the infrequent tokens by boosting their probabilities. See section 4.3 in this recent paper for some discussion of this effect (“anti-overconfidence”) existing the last MLP out layer.

- The model also can’t just represent unigram frequencies - it’s a dynamic $n$-gram monkey. It is likely representing a much more complex interaction for the low frequency tokens, such as possibly memorizing their appearances.

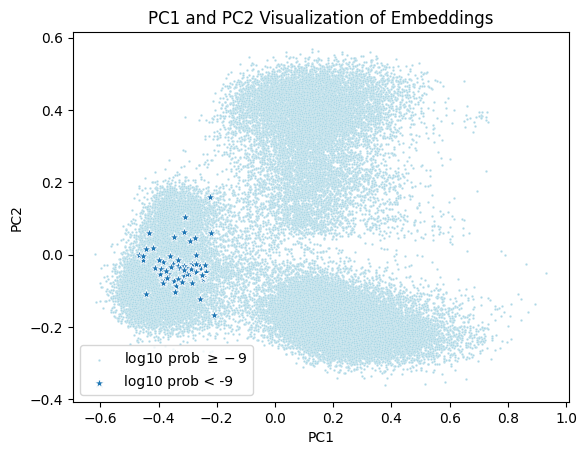

Regardless, we can see that the embedding matrix certainly treats extremely infrequent tokens differently than other tokens. Using PCA, we can also see that, in embedding space, the extremely infrequent tokens are all somewhat clumped together, further corroborating this idea that there’s some special subspace they’re all getting dumped in.

Over Training and Model Size

We can apply this technique to different model sizes and over training time.

| Checkpoint | medium-a Final KL Divergence | small-a Final KL Divergence |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7.78 | 11.42 |

| 100 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

| 1k | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| 10k | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| 100k | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| 400k | 0.08 | 0.07 |

The key observation here is that model size doesn’t seem to affect how well the embedding matrix represents unigram frequencies. This makes sense - all of these models have surpassed a “sufficient” capability threshold to represent unigram frequencies. We also see that the smaller model seems to develop a strong unigram frequency representation slightly earlier (see the difference at 10k). Intuitively, it doesn’t take a lot to represent unigram frequencies, so having less parameters to tune toward this first-order statistic probably makes this representation emerge earlier.

There’s also a unique behavior in gpt2-small where in early checkpoints, there’s a “bump” in its unigram frequency representation strength from 100 -> 10k. Probably a sign that something happened in those early steps, but I’m not too sure.

Takeaways

- A simple probe can reveal cutoffs for where models start to fall off in their embedding representations of unigram frequencies.

- Models treat these tokens distinctly differently than other, more common ones.

- Smaller models might develop unigram frequency representations faster.

- Adversarial robustness is one of the most challenging problems in AI right now because of limitations like dealing with long tails. But, it’s also one of the most important for both capabilities and safety advancement.

-

My training configuration: Adam with learning rate $0.01$ for 1e5 iterations - although the loss converges extremely quickly. I use $x_0 = \mathbf{0} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_m}$. ↩

-

For some reason, I found that entropy-based losses (CE and KL div) did not work nearly as well. ↩

-

The anomalous point around (-4, -8) is the BOS token

|<endoftext>|. This makes sense - the embedding matrix is basically treating it as a token that should never appear again. ↩