On Being Mortal

First post in half a year and a bit of a longer one. I recently finished the book Being Mortal by Dr. Atul Gawande - one of the first books I’ve read cover to cover in recent memory.

I would like to preface this entire post by saying that I am not a premed student, a doctor, or anyone with significant experience working in the life sciences beyond dissecting a squid in 8th grade and maybe high school biology + a taste of organic chemistry. But, I still thought that it would be cool to share the many thoughts that have spawned in my head since finishing the book, especially because the ideas presented in the book address and grapple with death, a topic for which I think most of us would like to avoid talking about because it is uncomfortable. However, I think Gawande provides strong evidence to guide us toward embracing these difficult conversations instead of worming out of them.

The book discusses confronting mortality and follows an anecdotal analysis structure where Gawande presents insights drawn from his own experiences on how doctors should help their patients who have to grapple with the looming presence of mortality - that they can’t live forever.

It is no overly profound statement to claim that I, and most likely most of humanity, take life for granted. I’m reminded of a Band Perry lyric:

“When you’re young, life’s a dream; it's a beautiful and a burning thing.”

When we are healthy and young, we are invincible, we can fly, and we believe we can do anything we want. But, we never, ever once genuinely fear that our time is coming soon (fear is the key word) or that the fire will suddenly be blown out, much less living in constant fear. It is not until all of a sudden that we do, usually incited by some significant effect occurring: chronic pain, loss of proper body functionality (blurry vision, loss of hearing), or terminal illness. Sometimes we see it happening to others; other times, it happens to us. In essence, we experience a sharp and sudden slap back into the reality of being a living being with cells that inevitably fail to function. It really is just the flip of a switch: we are immortal until we aren’t. We can break every wall in our way, always persevering and facing challenges head on, until in a blink we are faced with the unbeatable, unscalable, unbreakable, and unstoppable wall of mortality. Mortality has been there all along, hiding in the calm waters of the ocean until it becomes a tsunami. And the truth is, we are wholly unprepared, as both patients and doctors, to deal with it.

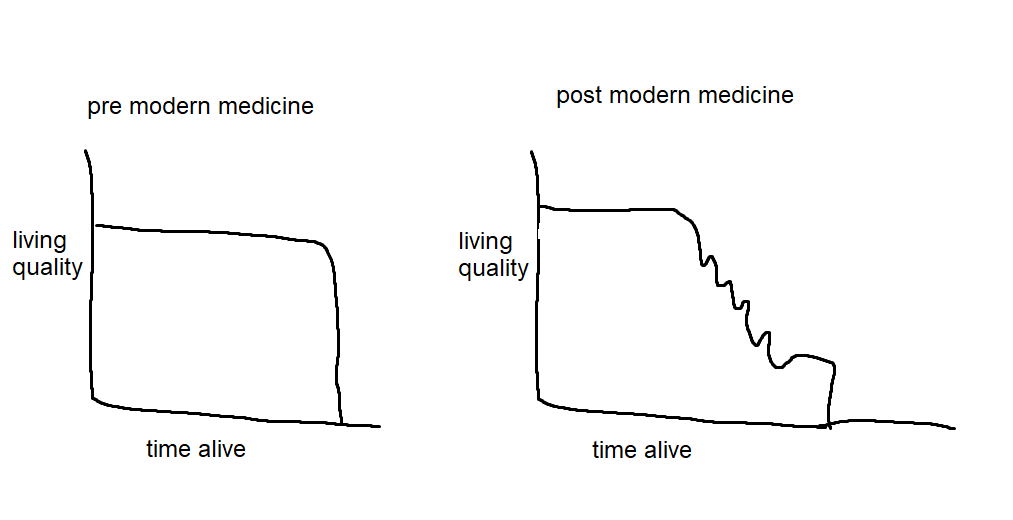

Pre modern medicine, there really are no words to describe the descent of human health other than sudden. Once you got sick, you were screwed unless you had a stroke of luck equivalent to winning the lottery. I can’t find the exact page of the graphic, but Gawande had some really nice graphs depicting this - here’s my MS Paint illustration of what I remember.

Post modern medicine, we can extend a person’s life much longer through countless treatments and medical breakthroughs: examples include chemotherapy, new forms of surgery, and experimental drugs that have names that look like autogenerated Chrome passwords. However, equivalent exchange often holds true for these aggressive treatments, as the side effects and recovery periods can be brutal. Even worse, their effectiveness is often not known fully by even the doctors prescribing them. We arrive at a crossroads: how do we balance the harsh side effects of these treatments with prolonging God’s gift of life?

In the theoretical sciences, the hardest problems are muddy at first but can eventually become clear with enough research and time poured into them. Answers are answers, proofs are proofs - there is (mostly) no debating a correct or provably optimal answer. But, despite being unanimously agreed on as a science, medicine seems to be completely unique in that being a doctor means facing a constant barrage of decisions that do not have a correct or optimal answer. Additionally, (this is definitely debatable, but let's go with it) I think that sciences have the defining quality of being timeless (this idea originates from Platonism). The truths of science have always existed and will always exist, and have always been correct and will always be correct. Further, the truths of science are spatially invariant: they are true everywhere in the universe. Thus, it is quite a bit simpler to formulate decisions based on these invariant and strong truths in most sciences. However, medicine seems to present a challenge that the correct answer and decision change over time, vary globally, and depend on abstract concepts like access to resources and cultural values. And finally, a nontrivial amount of times, the optimal solution may not even exist.

In computer science in particular, the idea of optimization and existence of an “optimal” procedure to perform some task is key to numerous areas of study. It is the fundamental idea underlying modern deep learning (optimizing some loss/error function through gradients), algorithmic theory (optimizing complexity or other ideas like linear programming and convex optimization), and almost all of cryptographic security (making the optimal attack as slow as possible). Our heads are hardwired and attached to the following premise: given the conditions of a system, what is the best I can do with respect to some observable?

Let’s see what happens when we apply some mathematical optimization logic to medicine. We’re a doctor, approached by a patient. We are to prescribe pill A or pill B, and we want the most optimal choice.

Right off the bat, we notice that despite having a finite number of choices, problematically there seems to be an infinite number of outcomes measured on how well the patient does. No drug is \(100\%\) effective, and this inevitably causes one of the greatest flaws in medicine research - so much of it is never able to be replicated. Studies claim great numbers yet their work is often disregarded because everyone who tries to reproduce the work can’t get the same numbers as the original study. Drugs are deemed experimental and often never leave that stage because they fail to prove their efficacy on a larger or simply different sample.

A representative model of how to approach decisions using math is by basing the decisions on the expected outcome. It’s easiest to explain this in the context of a game like poker. A healthy bit of poker relies on playing in an “unexploitable” manner, or in a way such that you do not reveal any tendencies that could be exploited in your play, such as bluffing too many times or not playing enough hands. One important feature of “unexploitable” play is, of course, mathematically sound decisions. One example is the question: given my hand and what’s on the table right now, is calling my opponent’s bet mathematically sound in the long run i.e. does this bet lead to a profit for me if I play a bunch of hands? To answer this, one might consider various outcomes and their probabilities, and then add them up and make a decision based on how big the bet that their opponent placed was. There is always luck involved, so even if you make the best mathematical decision you might just get unlucky and lose anyway, but you can minimize luck’s influence over the span of many games played if you play in a mathematically optimal way (this is a concept in statistics known as the law of large numbers).

However, in medicine, of course, you are not playing a game. Looking past the obvious differences, I think the most crucial difference is that there is no “long run.” The law of large numbers does not apply when you are making decisions involving a person’s life, because as the saying goes, you only live once. You are all in on every hand, regardless of what you’ve been dealt. There is no \(\lim_{n \to \infty}\) involved. If you lose, you lose, and if you win, you only kind of win - mortality still will never go away, an incurable disease will not magically disappear. Even further, quantifying the “values” in the expected value is difficult if not impossible - what is the weight we assign to a situation where the patient lives vs. the situation where the patient survives, but is clearly at a lower quality of life? Everything we take for granted in math is completely useless in the treacherous wilderness of medical decisions.

I wrote the previous paragraphs with a bit of math jargon thrown around, but upon reflection, it could just be summed down in one simple question: what the heck do we even optimize?

I asked my friends a question just for fun previously that’s relevant: would you rather have emotions that have small variance or high variance? Implicitly hiding in that question is the idea that emotions can be quantified and that there is an optimal answer. But, what in the world does an emotion level of \(3\) mean? How do we establish an order on emotions? I’m willing to just flat out claim that it’s impossible to do for one person - forget even trying to provide a standard ordering or method of quantifying emotions that is universally applicable from person to person for all time. The same is true for evaluating the state of a patient. Even further, just like in physics, the reference frame matters - is it from the doctor’s point of view or the patients? Or maybe even an external observer, like a loved one? Every actor would provide a different evaluation of the situation, and I’m willing to bet in a mathematically sound manner that you can’t please all of them.

No wonder why so many doctors feel they fall short of expectations and suicide rates are proportionally higher in doctor populations. It is close to impossible to consistently make such decisions perfectly every time, and the impact of them is staggering in magnitude, with no one else to blame. I think this leads to many defaulting to the behavior that Gawande calls Dr. Informative - they know and happily distribute all the information about all the options, but fail to help their patients make the decision that will in the end best reflect both parties' desires out of an innate fear of loss.

I am not a doctor, but my gut feeling is that many adopt this position because they fall short at one key step: recognizing their patient’s values, which Gawande corroborates. Trained professionals are taught how to save lives and often automatically assume their patients have the same core value as them: dying must be avoided at all costs. In math, we can represent this ideology through assigning death a negative infinity weight and then just proceed using an imaginary average over all outcomes. Since no probability, no matter how small, will shrink the magnitude of dying, the doctors end up trying anything to avoid death (often supported by the patient and their loved ones), praying and hoping for the miracle treatment that suddenly works which results in the stark and volatile graph shown in the earlier image representing quality of life in modern medicine. Experimental treatments, extremely invasive surgeries, and other aggressive treatment methods often leave patients disoriented, bedridden, and unconscious, but hey, we avoided death, right?

When death comes knocking on the door, a person’s values shrink greatly. When they wake up, look out their window, and see the massive tsunami barreling into shore, their horizons shrink and hyperfocus on what they value the most: often it's loved ones or other activities they have done all their life. For others, it's being able to live on their own. I distinctly remember that Gawande encountered one grandfather who really just wanted to be able to eat chocolate ice cream and watch TV. Regardless of the situation, Gawande’s anecdotes revealed that these values are often so important to his patients that they would rather live shorter but be able to speak to their grandchildren than live the remainder of the prolonged (!!) life bedridden, unconscious, and unable to live without lines and tubes of medical equipment dangling out of them. In plain words, the doctors could not be more wrong and in the end inflict more pain than they resolve.

Thus, we arrive at the only way forward to address the seemingly desperate and turbulent lose lose situation of confronting mortality.

The most powerful tool at a doctor’s discretion is not their scalpel or their stethoscope, but rather their mouth and ears. It is their power to communicate.(I blockquoted that even though I wrote it because that was fire.) A doctor must be able to communicate with their patients on what is most important to them, no matter how difficult the conversation may be, simply because otherwise there is too much variance introduced to the situation that it is merely impossible to optimize. Such conversations take extreme effort, care, and often time - weeks or months, and need to not only occur between the doctors but also with loved ones.

I think this gap between simply knowing the truths about medicine and being a doctor will be the most difficult challenge of introducing AI into medicine and why I believe that a doctor’s job is one of which is not going anywhere, despite significant machine learning advances in both classification and regression tasks related to medicine. To be able to empathize and understand the unquantifiable quantity of human emotion and health is invaluable to mastering a profession in medicine that I don’t see AI being able to perform at a high level anytime soon, if ever. What kind of task even is that? It feels fundamentally flawed - how do you even approach formulating a concrete problem to solve? There’s just too many variables, too much variance - I refuse to believe that this level of complexity can be represented in a finite number of nonlinear functions that have been converged on by some neural networks. Even if you can get some combination of models that partially work, I can’t see a world where they generalize properly/don’t overfit on training data. But, please, somebody be my guest and prove me wrong.

I definitely had some grasp of this idea previously, but I think reading Gawande’s book has really opened my eyes to how much really goes into being an excellent doctor. It is so much more than knowing textbook facts or always being correct on which prescription is most effective in which scenario. These are important, but the added dimension of working with people introduces infinite complexity into an originally controllable and potentially mathematically representable system because people have feelings and values. Facts might not care about your feelings, but it is the role of the doctor to reach beyond the facts, the raw numbers, meaningless percentages, and instead foster a relationship to make the hard conversations with their patients and discuss what truly matters when life has abruptly been placed on the clock.

As I scramle to find a proper way to end this long post, I can only think of this one line from the book that particularly struck a chord with me. It went something along the lines of “life is a story, and endings of stories matter above all.” That’s definitely the wrong wording, but it’s the right idea. Watching a TV show that builds up great and then bombs the ending is one of the worst experiences, particularly fueled by our tendency to have recency bias. Clearly, in medicine, the endings of life stories can hardly be dictated, predicted, or controlled. But, through crucial communication, we can still do our best to make do, recognize when enough is enough and what is of utmost importance at the end, and let people be the authors of the endings of their stories.

I really enjoyed reading this book and it gave me a lot to think about in the sweltering terrarium that is my house this summer 😂. I hope you enjoyed reading my overly wordy thoughts.