The Distribution of Skill and Imposter Syndrome

Inspired by a brief conversation with my friends that I had over 6 months ago...

When in doubt, it’s probably Gaussian - out of all distribution shapes, as far as I know the most common naturally occurring shape by far is the Bell curve, especially the normal distribution. But, I wanted to write about a distribution which I believe is definitely not Gaussian: the distribution of skill. I’ve been thinking about it recently because my younger friends are going through college apps right now and feeling all sorts of negative thoughts and doubts about their experience and ability.

Before getting to the core of the post, I think it’s good to lay out some foundational groundwork for later. Implicity hiding in the question of what the distribution of skill looks like is some sort of quantification of skill, so let’s start with answering that.

Quantifying Skill

Suppose we wanted to use some set $S_A$ to quantify “skill in activity $A$.” Here is my collection of sufficient or necessary properties of $S_A$, which is definitely not perfect but good enough in this scope.

- There needs to be a linear ordering on $S_A$. This is more of a property of $A$ - $A$ needs to be sufficiently “specific” such that we can compare any two given skill levels. 1 It’s hard to tell who’s better at “swimming”, but it’s a lot easier to tell who is better at “the 100 fly.”

-

$S_A$ should be both bounded above and below. One side is easier to motivate than the other.

- Bounded below: “No skill” in activity $A$ is the lower bound, which I feel is pretty natural.

- Bounded above: On the other hand, this could be slightly subjective and feel free to call me a pessimist/doubter/hater. But, I believe that humans have an inherent limit to how good they can get at doing $A$ just by being human with a human body and a human brain.

- $S_A$ should have a natural metric defined on it. This need not always be true, but for the purposes of this post we need some way to quantify the distance in skill between person $1$ and person $2$.

- $S_A$ should not be discrete. Using the metric from (2), we can define discrete as for all $x \in S$, there exists some $\delta > 0$ such that $B_\delta(x)$ (the ball of size $\delta$ around $x$) does not contain any other points in $S$ - in essence, it should be possible to asymptotically approach some skill level.

Probably too complex of a definition since $S_A$ isn’t super important, but I thought it would be nice to be rigorous. Using these properties, we can define an injective mapping $\phi : S_A \to [0, M]$ for some $M > 0$, where $\phi$ is an isometry (preserves the metric, with the metric on $[0, M]$ being $d(x, y) = |x - y|$) and monotone (preserves the ordering, with the ordering on $[0, M]$ being $\leq$). 2

The Distribution of Skill

Disclaimer: from now on, I will state ideas as if they were exact, but in reality everything is extremely approximate and handwavy. There will be a lot of abuse of notation and the devil is 100% in the details. This is mostly because I am not sure of the details myself :P.

The only evidence I have to support motivate the following section is all empirical, but bear with me a bit. Speaking from my own experience as a competitive swimmer that was (hopefully) above average in skill level, even as I progressed forward, it always still felt like there was always somebody to chase. Through talking with my friends who I looked up to, I realized that they also felt the same. This feeling was mirrored in competitive gaming - even as a top 1% player in a game who can dominate an average player, I could still easily get demolished by any top 0.1% player.

Put simply, the people who are at the top are insanely good. Like, unfathomably good. The skill gap between someone in the top 0.1% and someone in the top 5% is similar to the gap between someone in the top 5% and a complete beginner. That existence of legends like Michael Phelps, Tiger Woods, Wayne Gretzky, and Serena Williams - people who at their peaks were untouchable - motivates further discussion. These were people who made seasoned professionals look like they had never done the activity for a day in their lives.

The best are so good that I would argue that the Dunning-Kruger effect extends beyond just the initial hit to confidence in skill - at any skill level, there exists an upper bound to the skill that you can fully grasp and appreciate. To me, one must surpass a threshold to even begin to grasp how skilled the best are. Unfortunately, this necessitates a persistent and overbearing diminishing factor on the perception of our skill - we always think we aren't as good as we actually are.

We realize the shape of the distribution must have a long tail to account for these anomalies and also a large concentration of people near or around $0$ skill. Thus, clearly this cannot be a Gaussian shape, so what is it?

To me, the answer lies in approximating the feeling of “always having somebody to chase.” One simple way is to use the memoryless property, which states that if $X$ is our random variable of skill, $$P(X > t + s | X > s) = P(X > t).$$ Why does this match the aforementioned intuition? I think it’s best explained by a concrete example. Consider some skill level $s \in [0, M]$ in activity $A$. In our context, the memoryless property states that if I met someone that I knew was of at least skill $s$ (maybe we're at a convention full of people particularly skilled at $A$, or working in a job with a competitive application process, or attending a prestigious university etc.), the probability that they are at least $t$ points above $s$ is the same as the probability that a random person walking down the street was at least of skill level $t$ in activity $A$. The phrasing can be twisted into a pessimistic tone but with an apparent message if we consider $s$ as our skill:

No matter how much you progress in skill, the distribution of people above you is the same as if you had never progressed at all....which I feel is surprisingly accurate in light of imposter syndrome (more on this later).

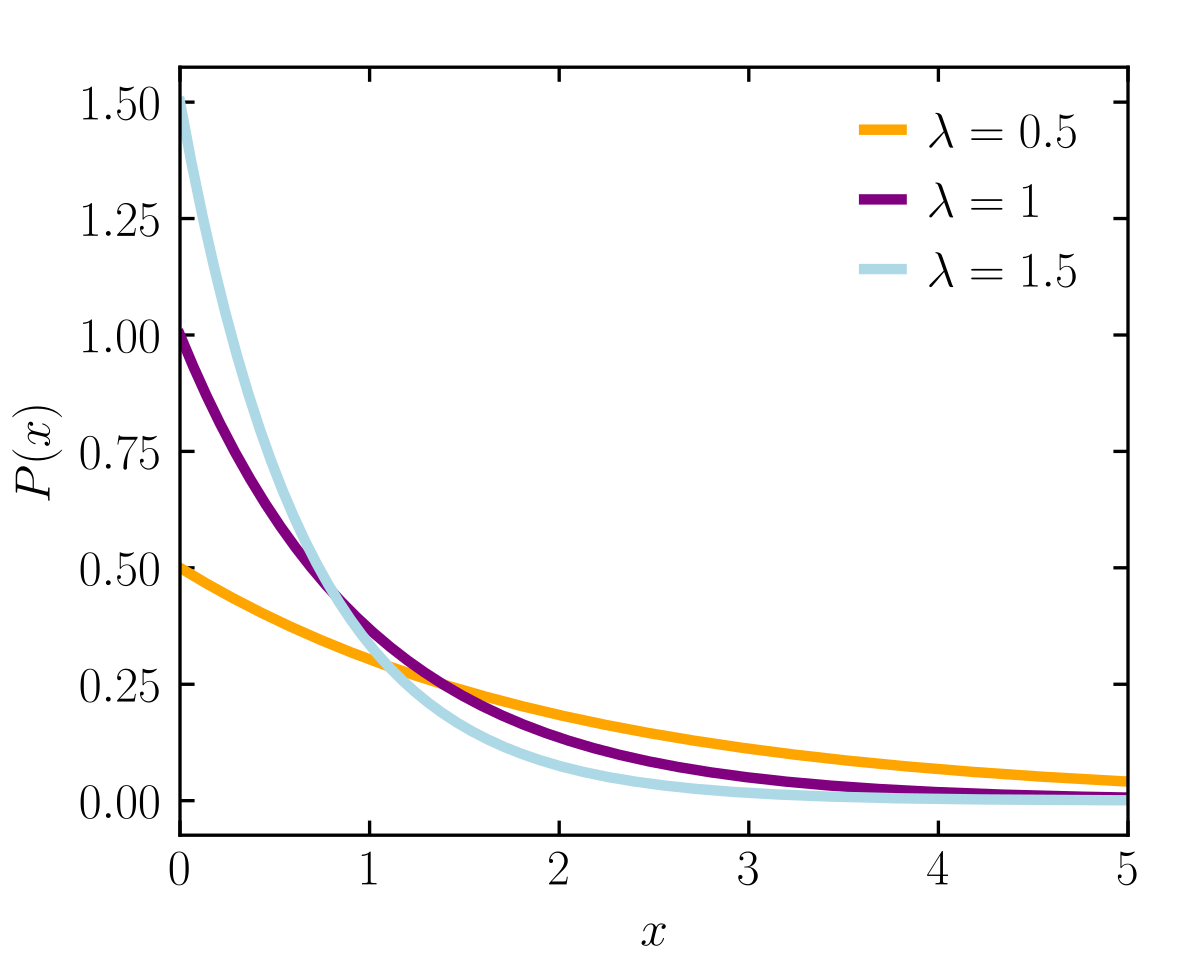

The only continuous distribution (which we need, since $S_A$ is not discrete) with this property is the exponential distribution, whose density function $f(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x}$ exactly fits our prior beliefs on what the shape should look like, as shown from the graph below shamelessly stolen from Wikipedia.

Armed with the quantification of skill and this incriminating evidence, we can conclude the distribution of skill can be most closely approximated with an exponential distribution, which explains the existence of imposter syndrome.

Imposter Syndrome

I’m not sure what the exact takeaway of this post should be, but I think it boils down to imposter syndrome being an universal feeling simply because of the shape of the distribution of skill. It can be both a blessing and a curse, as my belief is that having someone there to push and inspire you is one of the best ways to break through your perceived limits of skill and achieve what you could not alone. Anybody who has tried to do a swim practice alone knows this - it’s just different when there’s other people around. But, at the same time, the memoryless nature of getting better at an activity can become self-destructive to your mental health.

I’m not a psychologist or behavioral scientist, but my understanding is that these feelings become exacerbated in environments filled with excellent people that are competitive. The feeling of falling behind or not being enough is widespread because everyone is at least in the top 10% of what they do.

This is interesting in particular to me because I’ve generally felt the environment at Brown to be quite uncompetitive - the vibe is significantly less cutthroat than other schools. My (potentially wrong) impression is that a large proportion of the student body is there to have a good time. Despite this, through interactions with students of various backgrounds, I’ve gathered that imposter syndrome is still a shared experience for everyone.

Truthfully, I don’t know what to say to people who are experiencing imposter syndrome, but I feel like the only way to shoo away the negative thoughts is to grow an ego. Not to the point where it becomes annoying to those around you, but enough to live with confidence, swagger, and unshakable belief that you belong. Upon reflection though, this idea sounds pretty naive - I’m basically saying “just don’t feel that way,” which is a million times easier than it sounds. Average CS major social skills lol.

But, at its core, I believe that acknowledging the widespread existence of imposter syndrome (due to the nature of the distribution of skill) - that nearly everyone feels this way, and it's completely normal (pun intended) to do so - gives a sense of calamity and mutual support. Above all, while it’s important to look forward to how far you can go, it’s equally as important to not lose sight of how far you’ve come, because I find that the latter can sometimes be even more inspiring than the former.

[1] Specificity can be formalized through an ordering on the set of all activities $\mathcal{A}$, where $A_1 \leq A_2$ if doing $A_1$ is a part of doing $A_2$. For example, 3 point shooting $\leq$ basketball.↩

[2] At the moment I don’t see any reason that we would need countability, but $[0, M] \cap \mathbb{Q}$ with the same metric and ordering would also work. Though, speaking of countability, the “injective” part of $\phi$ kinda falls apart if $\text{Card}(S_A) > \mathfrak{c}$, but allow me to be handwavy on that since the core essence of this excerpt is just the key properties of $S_A$.↩