Conformity Bias - A Bayesian View

Thanks to James Zhou for discussion that prompted an update to this post.

Is this a dog or a cat?

Suppose that we think it’s a dog (if I had to guess, I’d say so). We’re pretty confident - maybe even 100% confident. But, most likely we’ll have some doubt, since we don’t know everything about animals - maybe we’re more like 95% confident.

However, we just received some new information: $k$ strangers also looked at the same image, and they all think it’s a cat. How does this change our guess?

Bayes’ Theorem

Bayes’ Theorem can provide us a principled answer to how our beliefs should update. Let’s stick to the example: we think it’s a dog and we are told the $k$ others said it was a cat. Let $D$ be the event that the image is a dog and $C$ that it is a cat. Namely, our updated beliefs can be written as

\[\mathbb{P}(D \vert k \text{ others think } C) \sim \mathbb{P}(D) \mathbb{P}(k \text{ others think } C \vert D),\]and

\[\mathbb{P}(C \vert k \text{ others think } C) \sim \mathbb{P}(C) \mathbb{P}(k \text{ others think } C \vert C) \sim 1 - \mathbb{P}(D \vert k \text{ others think } C).\]Here, I’ll define some notation for simplicity. Let $q$ be our “self-confidence”, and $p$ be our confidence in other people being correct. We’ll consider these innate human “estimates” of how often we are right and how often other people are right. In particular, we know that $\mathbb{P}(D) = q$ and $ \mathbb{P}(1 \text{ other person thinks } C \vert C) = p$.

Since these are $k$ strangers, we’ll assume that we have the same confidence in all of them being correct ($p$). If we believe that they gave their responses independently, $\mathbb{P}(k \text{ others think } C \vert C) = p^k$ and $\mathbb{P}(k \text{ others think } D \vert C) = (1-p)^k$.

However, I think human psychology operates logarithmically and implicitly inserts a dependence structure - the difference between $1$ and $50$ people saying it’s a cat should not be treated the same as the difference between $50$ and $99$. So, instead, I’ll specify the joint pmf as

\[\mathbb{P}(i \text{ of } k \text{ others think } C \vert C) = M \binom{k}{i} p^{\log i}(1-p)^{\log (k-i)},\]where $M > 0$ is some constant that captures both the base of the logarithm and the normalization constant that aren’t really that important.

To be honest, I can’t really give a good justification for this modeling decision other than “I think it feels more right.” I also haven’t seen a common dependence structure that would actually result in a pmf like this, so it’s possible this is really stupid. If we just use $k$, then the results would be similar, just more aggressive. Anyway, let’s roll with it.

Our posteriors from before become

\[\mathbb{P}(D \vert k \text{ others think } C) \sim q(1-p)^{\log k}\]and

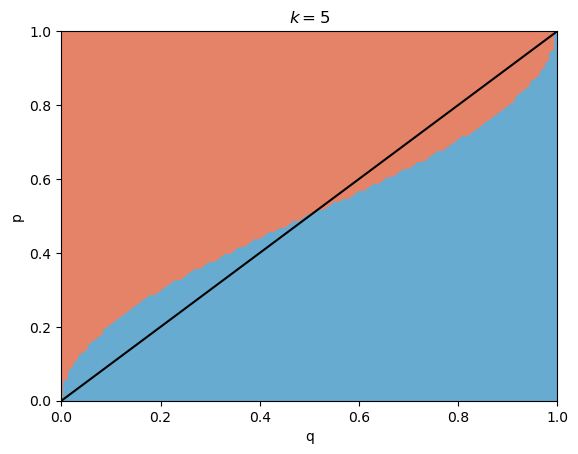

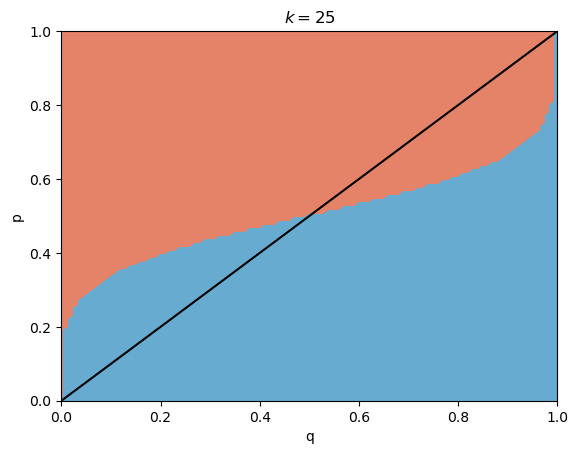

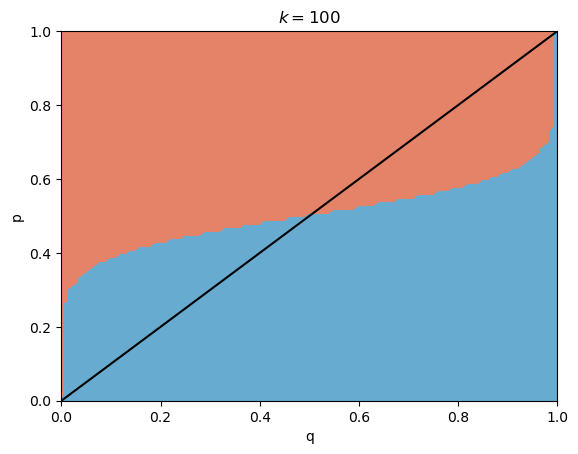

\[\mathbb{P}(C \vert k \text{ others think } C) \sim (1-q)(p)^{\log k}.\]We deviate from our original guess of a dog when the latter expression is greater than the first. I plotted this for various values of $p \in [0, 1]$, $q \in [0, 1]$, and $k = 5, 10, 100$ (arbitrarily chosen).

The red side represents switching to the cat guess and the blue side represents staying with the dog guess - the black line is $p=q$.

Suppose that we believe ourselves to be correct more often than not ($q > 0.5$). Note that there are many cases where even if $p < q$, because of the impact of $k$, we would rather switch than stay.

Conformity Bias

This setup is used in many conformity studies: the subject answers a prompt, such as this dog and cat example (though maybe not this obvious). Then, they are told the engineered guesses of some strangers who are intentionally disagreeing with them. The subject is then asked the same prompt again.

The interesting phenomenon is that many times the subject will change their guess, even if their original answer was correct and $k$ is small. It results in funny situations where even when it’s obvious that the other people are wrong, the subject still switches their answer. But why?

Using our framework, we can provide a few explanations for the subject switching, assuming the selected population can be generalized to humans as a whole.

- Humans are a very trustworthy species. A high $p$ will result in us switching our beliefs more often.

- Humans have low self-confidence. A lower $q$ will will also result in us switching our beliefs more often.

I don’t see either of these as particularly accurate. Making personal statements here: without good reason, I wouldn’t have high confidence in random strangers and I also tend to trust my own judgement. Through my probably-selection-biased assessment of my peers, this tends to be true for others as well.

There is some unaccounted effect that induces a relative increase in trust of others with respect to self-confidence. Equivalently, a relative decrease in self confidence with respect to confidence in others.

I believe this is exactly conformity bias. Because there is a perceived added benefit to conforming, we tend to want to blend in rather than stand out. This is probably conditioned through evolution - standing out from the crowd is as good as being dead.

We can try to measure this impact $I$ quantitatively through some desiderata/assumptions. In particular, we want to think of $I$ as the increase in trust in other people’s opinions relative to a default situation. Notably, I treat trust (somewhat unintuitively) as a separate quantity from confidence.

- If we have more trust in others, we place higher value on their opinions and a lower threshold in $p$ is needed to cause us to switch our opinion. So, if we fix $q$ and $k$, $I$ should be inversely related to the minimum $p$ that would cause us to cross the switching decision boundary.

- a) We have no reason to have trust in other people by default. b) If we have no trust in other people, even a $p$ of $1$ would not cause us to switch.

- If $k$ increases but $q$ is fixed, then $I$ should increase - more people should apply greater pressure to conform, inducing a higher artificial increase in trust.

Putting these properties together naively gives

\[I = 1 - \inf \{p : q(1-p)^{\log k} \geq (1-q)(p)^{\log k}\}.\]Notice that $I \in [0,1]$, with bigger meaning that social pressures to conform have a higher influence. If we compare the graphs with different $k$s, we can also observe property $3$.

I’m confident this is not the only way to define $I$ or think about it, but I think it’s a good starting point to get some intuition on quantifying conformity bias.

In particular, I have made the implicit assumption that humans are perfect Bayesian updaters and that the bias takes place in the inputs to the update. In practice this is impossible: with finitely many neurons in our brain, we cannot be perfectly Bayesian.

Furthermore, I’ve established a very cynical default state of $0$ trust. I don’t see in a truly random scenario how this could be changed, but in most real life scenarios a human (replace with agent) might encounter the other agents can probably be bucketed as trustworthy or untrustworthy.

Why This Matters

Not too sure. I do think it’s cool in the context of AI alignment though.

- A notable shortcoming of some LLMs is that they can be gaslighted into hallucinating particular answers to prompts, not unlike our poor subjects who are tricked by an engineered situation that brings out their conformity bias. Maybe there’s some way to “trick” a misaligned AI into believing it’s dumb and instead conforming its behavior to human values. For example, directly including a “social” regularization term into its objective that rewards it for fitting in.

- A worst-case rebuttal to (1): an AI can deceptively conform. It may learn to value conformity, regardless of its true “beliefs,” as a general behavior because its creators (us humans) are more likely to leave it alone to achieve its objective if it conforms. Actually, this effect probably already occurs in human studies - I’m sure that some of the subjects from the studies thought everyone else in the room was stupid. Now imagine that human replaced with a misaligned AI…