A Crazy Week in My Life

This post is quite stream of consciousness-y and a bit different. Starting at 5pm on February 16th, I had one of the most eventful weeks of my life, where a bunch of significant events all coincidentally landed on the same week. Normally I keep a private journal for events like this, but since as far as I can remember (outside of vacations) this was probably the most eventful week in university/potentially ever, I thought I'd write a post reflecting on it.

However, I decided against doing a detailed play by play of all the events that happened, because (1) to be honest I don’t really remember all the details and (2) I don’t think it would make for an interesting post. I'll just include some high level summaries and dedicate the bulk of the post to reflection on the first event (MCM), which was most impactful to me.

2/16-2/20: International MCM

Update (5/8/23): we won Meritorious Winner!

From 2/16 to 2/20, I participated in the International Mathematical Contest in Modeling with two friends, Alexey and Matthew. I got invited on a whim to join them after meeting Alexey since I'm also working on a research project with him, but to be honest I was initially hesitant to join because they are insanely smart, almost intimidatingly smart. More on this later.

On Thursday night, I moved into their room so that we could all be together for the duration of the contest. It was super funny interacting with them and I felt a weird excitement since I had never done anything like this before. Namely, I had never:

- Completely devoted a nontrivial continuous segment of time (nontrivial being above 5-6 hours) to solely thinking about a singular problem

- Pulled an all nighter to achieve (1)

- Slept over in someone else’s place of residence for longer than one night

I also felt quite a bit of pressure, since I had only recently met them but based on their backgrounds they were way ahead in coursework and knowledge than I am, which may be excusable in a normal problem solving contest, but in a contest that requires more knowledge like a modeling contest, the gap would be extremely apparent. To be completely honest, I went in with one core goal: to contribute a meaningful portion of the project and not just be a paper writing LaTeX slave.

Well, within the first few hours, my theories were confirmed: I was not going to be able to keep up easily. I thought about it more after the contest, but I think one of the biggest areas where I'm behind them is in being able to find relevant literature and good papers. I always end up bogged down in the details of some random stuff, but my teammates had a knack for being able to synthesize papers and collocate the ideas efficiently. The pursuit of rigor becomes a curse in time pressured contests like this, since I can only read through 2-3 papers at most but they’re able to slam through double digits and aggregate the ones that are relevant.

It’s not unlike problem solving - I would definitely classify this strength as a strength in intuition. Because they’ve read so many papers and are more familiar with techniques used at this level through coursework, they know what to look for and can search with better keywords than me.

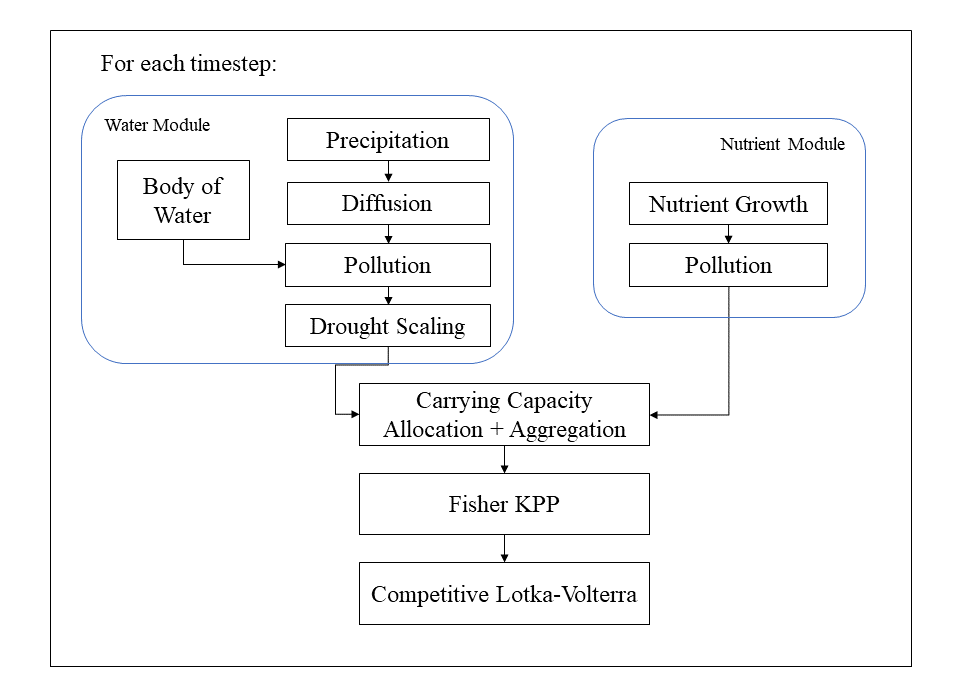

We chose to work on problem A, which was about how plant communities can adapt to survive through droughts depending on the number of species and the biodiversity of the system. Around 3-4 hours in they threw up legitimately an end to end pipeline on a whiteboard, and I found myself panicking a bit when this happened since I didn’t understand like 50-75% of the model specifics. The probability of me being useless had suddenly become magnitudes larger. Here’s an image from our paper describing our pipeline, in which the goal was to simulate a plant population's evolution over time in a complex environment.

I worked on the upper two modules (water module and nutrient module), where I designed some methods that we could simulate the growth and diffusion of resources in the environment, while accounting for pollution and droughts. My teammates cranked out the bottom half (which is appears to be less boxes but is significantly harder than what I had to do), where they coded up numerical methods to simulate competitive effects between populations of species (Lotka Volterra) and population diffusion (Fisher-KPP). We ended up using some simple finite difference method for the Fisher-KPP that was definitely suspicious because it unexpectedly turned out to be a monster equation, of which we later found out usually requires spectral Galerkin methods 1 .

The story has a semi-happy ending though: I ended up working on the environmental simulation components since that was closer to my familiarity zone of statistics and probability theory (we used a Possion-Gamma coupling to model precipitation events) while my teammates handled most of the numerics of the differential equations we were using. So, I did achieve my goal of contributing something meaningful.

Somehow, even though our stack is quite complicated, when we fit it together it actually worked quite well. Our biggest shortcoming was a failed parallelization attempt, which led to big issues later on as we tried to run case studies that were not computationally feasible without parallelization. It was pretty surreal at the end, as we worked all the way until 8pm on the dot on Monday. The project didn’t turn out as well as we had hoped since we weren’t able to answer all of the portions of the problem to their full extent, but I learned a ton and just had a really good time that weekend.

Reflection

1. Intimidation

Being intimidated proved to be a huge problem many times throughout this competition, especially in the beginning. I didn't say what I truly wanted to say and didn’t ask any questions because I feared that I was "bothering them” by just being dumb. Thinking back, it’s so stupid that I felt this way, but I can imagine that I’m not alone. Normally, I’m quite confident and not insecure in my abilities (I’ll fearlessly ask some seriously dumb questions sometimes in class), but placed in this new environment, all of that went out the window.

But, I felt a shift in mentality when I started realizing they didn't know all the details either. Me asking and provoking a discussion with them was incredibly valuable for both the purposes of us as a team designing a model but also my confidence. I can’t stress enough the boost in confidence every time when I got the courage to speak and it caused them to realize some insight or reconsider methodology, which I give huge props to them for. Even my idiotic questions that stemmed from just not knowing enough about differential equations sometimes exposed flaws in an implementation.

That was one source of confidence. For some people, when they drink alcohol (legally of course), they get “liquid courage” - I’m not sure about the neuroscience, but the way alcohol affects the brain also reduces the mind's ability to overthink and reduces inhibitions. For me, I think I got “lackofsleep courage.” Later on in the comp, as the ratio of hours awake to hours slept progressively increased, I think my mind, in an effort to preserve energy, let down its overthinking barriers and I ended up unconsciously speaking my thoughts way more often. In a sense, I was just too tired to overthink.

I would not recommend this as a method to anyone to stop overthinking though 💀.

2. Sleep

Another one of my biggest goals going into the contest was to push myself physically as much as I could. I’ve always been pretty safe when it comes to my body - I sleep early and eat three meals a day, largely because I was a student athlete for all of high school. But, I wanted to try to see what I could do when I pushed it to what appeared to be my "unhealthy" limits. So, here's a record of the sleep I got:

| Friday | 7am - 10am |

| Saturday | 8am - 9am |

| Monday | 4am - 7am |

| Total | 7 hours |

I don't want to be cocky, but the all nighters weren't that bad. Aided by my pretty healthy circadian rhythm, I actually felt quite decent throughout most of the competition. I’ve heard that hunger comes in waves, and I think tiredness is the same - there were just some stretches of 2-3 hours of waking time where I achieved very little because the tiredness hit me all at that point. Once I got past that wave, I’d feel normal again.

I lost a sense of time for sure - I stopped getting hungry at normal times, and eventually at the end I stopped getting tired at the normal times as well. I think my body kicked into overdrive mode and began ignoring basic needs to keep my brain operating.

There were definitely some weird things happening though. For instance, when I did decide to sleep, I’d set an alarm to not oversleep. Yet, somehow, I swear I woke up unconsciously, turned off the alarm, and immediately fell back asleep, because multiple times when I woke up, it was way past what I set an alarm for (luckily only by an hour at most if I remember correctly). Probably something to do with the sleep cycle, no clue.

Another thing is that my brain didn't feel slower at all, even though it definitely was. I’m pretty sure that my brain just simply shifted its time scale, so that even though my brain was definitely working slower, the time perception was the same. It was a facade that I felt like I was working at the same rate.

3. Lessons

As a final note to not drag on this section longer, I want to do a bullet list of things I learned or knew already but this experience reaffirmed:- I can pull all nighters. At this age, my body and mind are more resilient than I thought. On the same note, exposing myself to outside pressures clearly leads to discoveries about myself. Pretty proud of breaking this limit, as silly as it sounds. When they initially invited me, I almost fell victim to my mind almost worming myself out of this new and uncomfortable environment.

- More on intimidation: I think the solution is to forget about other people's thoughts about you. Ask all the questions you want and spit out all of your thoughts. In hindsight, I'd rather be perceived as someone dumb but know what's going on than to keep my silence and not know what's going on. In The Last Lecture (great book by the way), Randy Pausch, a Brown alumni and late professor at CMU, said he deeply admired a grad student that "wouldn’t leave a meeting until he understood everything," which I think is great quality to work toward.

- Taking the time to plan out an idea for a little extra time can save so much time later.

- Knowing when to throw out an idea vs. plow on for a little longer is crucial. I'm a big proponent of struggling, so I’m still horrible at this, as I tend to only give up when I feel like I really explored every single idea I could, but there's also this persistent feeling of “well what if I spent another hour and figured it out?” It’s kind of like a mix of gambler’s fallacy and sunken cost fallacy lol. Knowing when to cut losses is important.

- Expect to be sloppy and make tons of mistakes when coding/doing math on no sleep.

- Doing object oriented programming and then later needing to reread your own code on no sleep is a horrendous idea.

-

Specifically to this modeling competition at least, completion $\gg$ model complexity, generality, and fidelity. If you aren't able to answer the questions properly, you won’t win anything, no matter how beautiful your model is or how complex it is. Most winning submissions use incredibly simple ideas to ensure that they answer all the questions.

Alternatively, you can ascend beyond such trivial motivations of winning a competition and instead take risks to be creative and do whatever you want in pursuit of expanding your knowledge and maturing as a mathematician and problem solver… and maybe win as well.

I had a ton of fun and have no regrets in accepting to do this competition with Alexey and Matthew. I learned a ton about big ideas (approaches to modeling, numerical PDEs) and little ideas alike (there's generalizations of entropy??? [Hill Numbers]).

But, I think one of the most interesting and fun parts was just solving little problems throughout. With attacking a problem this general, we encountered many such cases - for example, at some point we wanted to generate a random $n \times n$ $\alpha$ matrix representing the competitive effects of $n$ species on each other for the competitive Lotka-Volterra model. The matrix needed 3 properties such that the solver would be stable, where $[n] = \{1, 2, \ldots, n\}$:

- For all $i \in [n]$, $\alpha_{ii} = 1$.

- For all $i \neq j$, $i, j \in [n]$, $\alpha_{ij} = \alpha_{ji} \in [0, 1]$.

- $\alpha$ is positive semi-definite i.e. for all column vectors $v \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $v^T \alpha v \geq 0$.

I came up with a really simple and elegant way to achieve this, inspired by the positive semi-definite properties of the Wishart ensemble from random matrix theory: just randomly generate a matrix $X$ that has all rows as unit vectors and compute $XX^T$. The proof this works relies completely on basic linear algebra facts and the Cauchy Schwarz inequality. It was a short and basic component in a much larger and complex model, but it was still a “oh that’s kind of cool” moment.

2/21, 2/22: Short Break

These days, I just caught up on sleep, homework, and practiced for ICPC coming up on Saturday. Very appreciated, but I still would have been fine without these rest days because I’m built like that.

2/23-2/24: Trip to Philly

Event number 2! I went to Philly for a business trip on these days. There’s not too much to say, as pretty much everything was exactly as expected, but I did have a first time: Thursday night was my first time in a hotel room alone. It was oddly lonely and eerie, but I slept great 😛.

Finally, on 2/25...

2/25: ICPC

On Saturday I drove up to College of Holy Cross (unfortunately couldn’t bag a spot at the MIT site this year) for my first ever in person programming contest (International Collegiate Programming Contest). I teamed with two other sophomores, Luke and Mohammad.

The competition was fun overall, but our team made a ton of silly mistakes, likely due to nerves and that none of us had been under the pressure of competing in-person for a programming contest before. For example, Problem I was a standard dynamic programming problem that we could have been first to solve, but instead took us forever to debug after we submitted a WA (wrong answer) because we just missed a small case when determining the valid transition states. These mistakes plagued us throughout.

This year's competition was super implementation heavy - the ideas weren't that tricky but the implementation was annoying. For example, Problem K was determining if two trees were the same (super easy idea, just sort nodes at each depth), but reading in the input was annoying, since the input formatted a tree as using parentheses: (10 (23 24)) represents a tree with root node 10 and (23, 24) as its children.

Personally, I’m not a fan of these types of problems as I prefer when the the difficulty of problems stems from the problem itself but it is what it is. We ended up with 7 solves, which was good enough for 12th place in our region. Unfortunately for us but congratulations to them, another Brown team consisting of some graduate students popped off and was able to qualify for NAC. Even if they didn’t exist, we would have needed to have committed many fewer sillies and solved the one problem we misread, but it was doable. Not the best, but I’ll be sure to grind for next year.

It started snowing during the competition, but as I came out of the final awards room I felt a sudden sense of relief that a long stretch was over. It felt a little melancholic and bittersweet (though I could be being too dramatic here). The sleep on the Uber ride on the way back for real hit lol.

Jeez, that was quite long. Thanks for reading, if you made it 🙂

[1] Yeah, that's just words to me too.↩