White Strokes - A Model of Evaluating Competence

I came across this old but great post from Eric Neyman this past week. In particular, he discusses one particular bias that I can relate to:

I tend to underestimate the competence of people who think very differently from me.

I think this effect is related to an inability to properly comprehend the effort required to achieve competence and finely distinguish between levels of competence.

I believe these effects are because humans are terrible at empathizing without a personal reference frame. This post is a discussion of my anecdotal evidence of these cognitive deficiencies and an attempt to offer a mathematical semi-formalization.

I’m going to use a lot of “I” statements here to speak from my own experience to avoid unintentional projection. It’s possible I’m the only one that feels this way - but through interactions on an interdisciplinary college campus, I have evidence to believe I’m not.

Woman with a Parasol

This past winter break, my aunt came to visit us in DC. She’s retired and spends most of her time painting. Naturally, the only thing she wanted to see in DC was the National Gallery of Art.

The night she came back from visiting the museum, I asked how it was and if she got to see anything else in DC. She told me that she hadn’t even finished looking through one floor of the museum yet and wanted to go back the day after to visit again! I was shocked - when I go to art museums with my family, we can easily leave satisfied after a few hours, having browsed the entire collection. I wondered how she could spend so much time looking at just a few pieces of art.

My disbelief was soon answered. When I asked which work she had spent the most time looking at, she told me it was Monet’s “Woman with a Parasol.”

Upon request, she passionately explained the countless different techniques she observed in the painting - I distinctly remember her describing to me in Chinese how, very roughly paraphrased:

"From far away, the sun shines and glistens on the woman's dress. But from up close, Monet has just masterfully placed a few small white strokes at these particular angles, resulting in what you see from far away."

I would have never noticed. But because my aunt has a personal reference frame of being a painter, not only can she notice these minor details, but she also knows and understands how those few white strokes are quite literally strokes of genius. Through her own struggles with capturing light in a painting, she has a much stronger and tangible grasp on the level of skill of Monet. Even after being made aware that the white strokes exist, I feel like I am unable to experience the same amount of awe and admiration that my aunt does of the work.

A Quanta-based Model

To summarize the above, these are the effects that I’ve empirically observed that I feel are root causes of Eric’s observation.

- I have no reference frame of how much effort it would take to achieve a certain skill level in a task that I am not skilled in.

- I am unable to properly distinguish between the skill levels of people participating in this unfamiliar task.

- Thus, I tend to underestimate the competence of people who think differently than me.

I attempt to capture the essence of these effects formally. To do this, similar to this paper, I’ll use a “quanta” based approach to cognitive task decomposition. A quanta is just a “basic skill” - in the paper, it’s defined as a basic skill of an AI model that is required for some task. I quite like this approach of decomposing tasks and will use the term synonymously.

Consider, for some task or activity, that there is some set of quanta $Q = \{q_i\}_{i=1}^N$, where $N > 0$ and can be infinite. Suppose for simplicity that these quanta are binary i.e. either it is acquired or not. This lets us model the acquired quanta as a set.

Each person has a set of acquired quanta $\mathcal{A}$ and a set of distinguishable quanta $\mathcal{D}$, or the set of quanta $q \in Q$ of which this person can distinguish between someone with $q \in \mathcal{A}$ and someone with $q \notin \mathcal{A}$ . The first property I require is that $\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{D}$ - the set of distinguishable quanta contains all of the acquired quanta. This is the only requirement on $\mathcal{A}$ and $\mathcal{D}$ - in reality, we can also pose a stronger requirement that

\[\mathcal{D} = f(\mathcal{A}), f : \mathcal{P}(Q) \to \mathcal{P}(Q),\]for some monotonic $f$ i.e.

\[\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{A}' \implies f(\mathcal{A}) \subset f(\mathcal{A}').\]The nice thing about this setup is that we can describe what it means to “fully appreciate someone’s competence,” posing some interesting questions:

- For someone’s acquired set $\mathcal{A}’$, is $\mathcal{A}’ \subset \mathcal{D}$?

- (Minimal covering problem) If we require that $\mathcal{D}$ is a map of $\mathcal{A}$, what is the minimal $\mathcal{A}$ so that $\mathcal{A}’ \subset f(\mathcal{A})$ i.e. allow me to fully appreciate the other person?

Dependency DAG

A particular example in this framework is if we defined a dependency DAG $G = (Q, E)$, where $Q$ is the set of quanta and $E$ is the set of edges, where the edge $(q_i, q_j)$ exists iff $q_i$ is a “prerequisite” to acquiring $q_j$ ($q_j \in \mathcal{A} \implies q_i \in \mathcal{A}$). This example is like a skill tree in RPGs (but it need not be a tree in the graph theory sense) or a course plan in college.

Then, one possible definition of $f$ is as follows:

\[f(\mathcal{A}) = \mathcal{A} \cup \bigcup_{\alpha \in \mathcal{A}} \{q : (\alpha, q) \in E\}\]i.e. $\mathcal{A}$ and all of its directly adjacent, yet not-necessarily-acquired quanta.

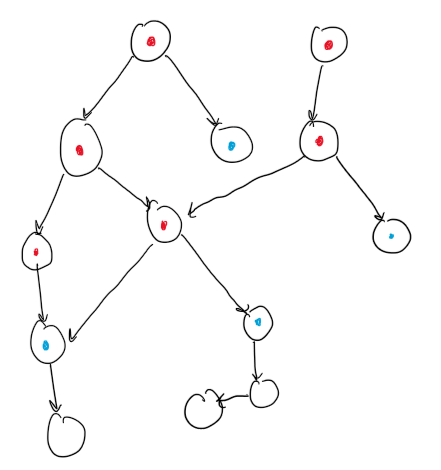

All points with a red dot are in $\mathcal{A}$. The points in red and the point in blue are $\mathcal{D}$ defined using the $f$ above.

All points with a red dot are in $\mathcal{A}$. The points in red and the point in blue are $\mathcal{D}$ defined using the $f$ above.

This particular $f$ is equivalent to finding a dominating set of $\mathcal{A}’$. In general, I think this is NP-hard even for DAGs, but for trees it can be solved in polytime using DP.

For particular structures of $Q$, we can specify lower bounds on this minimal $\mathcal{A}$ - for example, if $Q$ is a complete binary tree, we know (very, very weakly) that $|\mathcal{A}| \geq |\mathcal{A}’| / 3$ - we have to at least have acquired half the quanta that the other person has in order to fully appreciate them. The denominator shrinks as $\mathcal{A}’$ grows in size - as the other person is more skilled, we ourselves must be more skilled as well and be able to distinguish a greater proportion of their quanta.

The Skill Map

Let’s take this formalism one step further by defining a 1D skill map $s : \mathcal{P}(Q) \to \mathbb{R}^+$, that maps acquired quanta to some quantification of “skill.” I have written some desirable properties of $s$ in a previous post (not using the quanta formalism), but here the main additional property we need is monotonicity: if $\mathcal{A} \subset \mathcal{A}’$, then we require that $s(\mathcal{A}) \leq s(\mathcal{A}’)$.

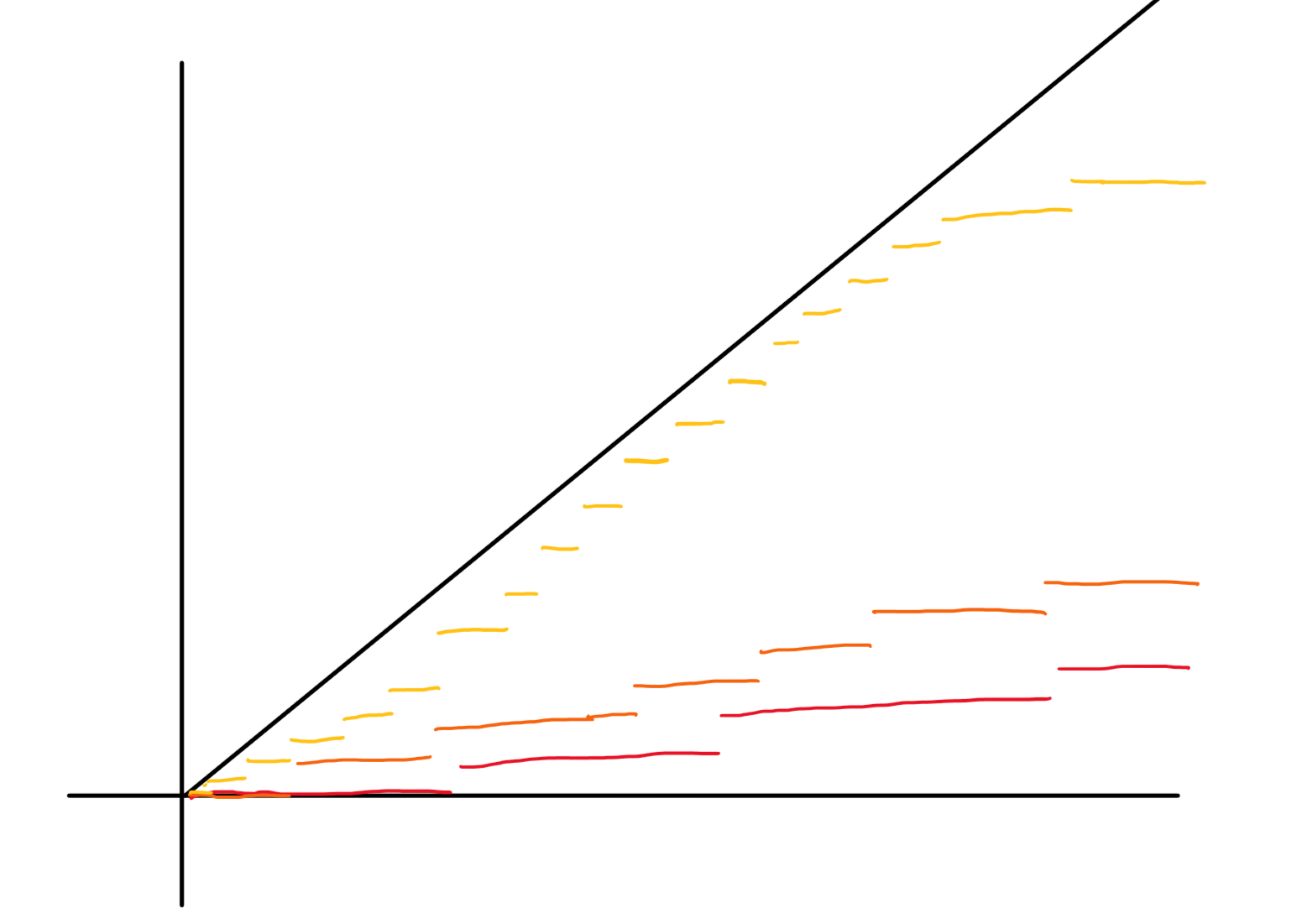

We can use this $s$ to make some interesting insights into how we could more deeply study the relationship between the skill we can perceive and the skill we’ve acquired. In particular, for a fixed set of personally acquired quanta $\mathcal{A}$ and distinguished quanta $\mathcal{D}$, we can create a graph comparing the skill we perceive of others versus their true skill.

More specifically, on the $x$ axis, we will have the other person’s true skill, or $s(\mathcal{A}’)$. On the $y$-axis, we will plot our perceived skill of them, or

\[s(\mathcal{A}' \cap \mathcal{D})\]i.e. how many of their quanta can we distinguish. We notice that all points lie under the $y = x$ line by monotonicity. This graph clearly depends on $\mathcal{D}$, and if we accept the idea that $\mathcal{D} = f(\mathcal{A})$, $\mathcal{A}$ as well.

Essentially, we expect this graph to, as we expand our skill and perception ($|\mathcal{D}| \to N$), to approach $y = x$ i.e. we have a perfect mental representation of everyone’s skill. I’ve drawn an example progression.

The red line is your initial perception - orange and yellow are as you progress further. Two observations that are shown:

- We achieve a finer perception as our skill increases

- We systematically underestimate competencies

To recall, these were the root causes I proposed and Eric’s conclusion:

- I have no reference frame of how much effort it would take to achieve a certain skill level in a task that I am not skilled in.

- I am unable to properly distinguish between the skill levels of people participating in this unfamiliar task.

- Thus, I tend to underestimate the competence of people who think differently than me.

We can see that this formalism accounts for all of these through $\mathcal{D}$, which captures the idea of a “reference frame” as the distinguishable quanta.

- In a task I’m unfamiliar with, $\mathcal{D}$ is a very small subset of $Q$ - I don’t have a good reference frame, so I cannot distinguish most of their quanta.

- If $\mathcal{D}$ is a very small subset of $Q$, I can only tell people apart at a very coarse granularity.

- If $\mathcal{D}$ has low overlap with someone else’s $\mathcal{A}’$, I will perceive them as being only as skilled as someone with just the skills $\mathcal{D} \cap \mathcal{A}’$, thereby underestimating their competence.

Sad Truths

Unfortunately, in my lifetime, I can’t achieve any semblance of this $\lim_{|\mathcal{D}| \to N}$ and truthfully that’s a bit depressing. 1

When I watch football, I know I can’t distinguish a system quarterback from one who a counterfactual difference maker. When I stumble through the city or an art museum, I’m blind to all of the intricacies and techniques being used in architecture and art despite being “immersed”. When I eat at a restaurant, I’m probably unable to notice the different taste “notes” of the meal or the masterful plating 2. These are human achievements imbued with mastery and finesse that I would like to appreciate, but with finite time I know I can’t get to them all.

But, this is also comforting. There’s always a wealth of knowledge and quanta out there to acquire - I just need to seek it out. The best I can do is try my best to expand my horizons, while acknowledging that my appreciation of others’ knowledge, abilities, and competencies, is probably poorly calibrated and work to keep an open mind to adjust accordingly.

-

An AI might be able to though… ↩

-

The first time I ever went to a Michelin Star restaurant was in Paris. I was served some sort of leek salad with edible flowers and a fried egg yolk. In the moment, I said that “I have no clue what I’m eating but this is fire.” My friends still make fun of me for this, but it captures exactly what I mean - I can tell that the food is good, but I am physically and mentally unable to have a deeper appreciation of the minute details. ↩